David Lynch Is the Greatest Artist of All Time, and We Must Never Let Him Die

The Magician who saw America's postwar shadow has died, while his city burns and his country is soon to. Can we carry his golden light in darkness — or is the future past?

(This piece includes spoilers of an aesthetic and thematic nature for various works of David Lynch, but contains no unmarked plot or story spoilers.)

“Bestie, the terrible day we knew was going to come is here”

I woke to find this ominous text from my dear friend Reina, whom I’ve never met.

“He’s gone. David Lynch died”

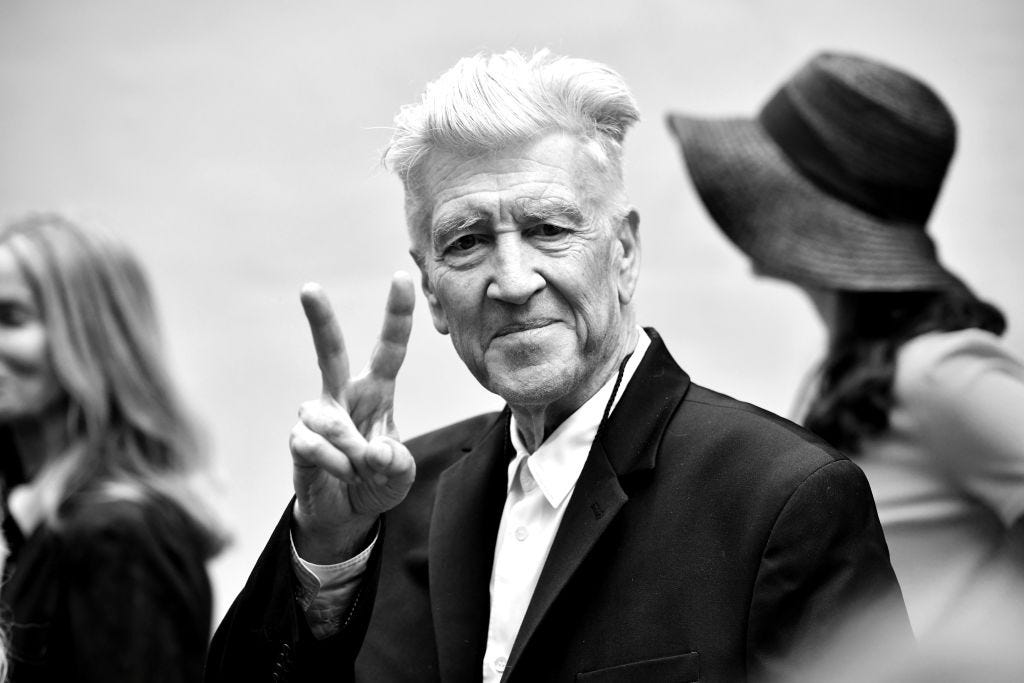

The artist who most changed the direction of my life and my work. My artistic and spiritual North Star for well over twenty years. My greatest teacher in this lifetime. The closest thing I’ve ever had to a mentor; the last and only person I would call my hero.

He’s dead.

Wrapped in plastic.

It’s such a sadness. Yet it’s also fostered a beautiful moment of increasingly rare cultural unity, as bittersweet and poignant as many of his most powerful scenes. Over the past three days, the entire world has been abuzz with personal, loving tributes to the artist who has most defined and redefined cinema for nearly half of its history. These speak to not just his artistic vision, but his humanity; his integrity; his kindness.

Friends who have bonded over his work are intimately holding space for each other’s grief. Many of us are discovering that even more of our circles than we realized share a love of his work. And we now have piece after piece of inevitable confirmation that seemingly every artist who’s done anything interesting or impactful in the past forty years — since, at latest, Blue Velvet — has been heavily inspired by his singular voice.

The outpouring of love, admiration, respect, and deeply personal connections from people of all walks of life, including artists of every medium, genre, and generation, is a rare mark of a life not just well lived — but a life really, really, really lived.

As I type these words, it’s finally hitting me. I am wailing out loud in grief.

“The tears are real. What is this thing called a tear?”

But to put my trust one more time in the one who showed me the deep, intrinsically spiritual meaning and potential of art, I will speak of him, forever, in the present tense.

David Lynch has altered and shaped the course of my life in an incalculable way. My craft as an artist and storyteller is inseparable from his impact and his model. I’ve written about him, spoken about him, frequented and performed in events about him. I run a highly active group chat all about him. Everyone who knows me, knows that David Lynch’s star burns bright in my Universe in a way that no one else’s ever will.

Outside of screenplays, this is the longest piece I’ve written in years. And I may not be Kale or Tidbit or Madgekin or Buttercup (yet). But your hero, and a historic visionary like him, only dies once (per lifetime). So I invite you to join me as I sprawl out like the lost highways of LA in celebration both personal and universal of the best to ever do it.

Because David Lynch is more than a man.

David Lynch is more than a filmmaker.

David Lynch is more, even, than an artist.

David Lynch is the Shaman of our time.

David Lynch is the great, definitive spiritual chronicler of the post-World War II American collective unconscious.

David Lynch is a Magician. A healer. A visionary in the most literal sense, which is the most mystical sense, whose intuition is deeply in tune with our collective conscience.

He’s peered into the darkness of the postwar America he loves, and seen its shadow. He holds a mirror up to us, inviting us to do our part in the shadow work we share.

I think a lot about the fact that David Lynch was born on Inauguration Day.

Specifically, the year after Harry S. Truman was first inaugurated.

The first one after World War II finally, officially came to an end.

Just months after the United States dropped the atomic bombs.

I think a lot about how that must have shaped his consciousness. This is pointed at starkly by many of the themes, allusions, and direct images in his work — especially whenever he works in the world of Twin Peaks with one of his defining collaborators, Mark Frost, another story-Shaman deeply invested in a psychospiritual lens on history.

It feels tragically fitting that David Lynch’s golden light finally leaves his body during a historically devastating climate crime against his beloved chosen home, Los Angeles, just days before an Inauguration Day that will mark a frightening new age of violent unmasking in his beloved country. To quote Reina again, just over 24 hours later:

“I’m still reeling over the fact that they took him from his home and it killed him. Uprooted him like a tree”

My thoughts, frankly, veer even more grim. In a sense, I’m glad he doesn’t have to witness what’s to come. That he doesn’t have to spend his 79th birthday uprooted, as LA County’s ten million working people suffer at the hands of billionaires and then get blamed for it because the media only depicts a few celebrities’ houses burning.

In a sense, I’m relieved he doesn’t have to spend his 79th birthday, wondering if it’s his last, while watching a genocidal, potentially totalitarian fascism metastasize into power under “the man behind the mask” — as potential sparks for a World War III dance like matches flicked at a haunted gas station that reeks of scorched engine oil.

Gentlemen, when two separate events occur simultaneously pertaining to the same object of inquiry, we must always pay strict attention.

We were all blessed to live in David Lynch’s time.

In so many senses, that time is over.

His birth and his death perfectly mark off the start and end of a distinct postwar end-of-empire zeitgeist. An age for which he has been the exact right individual, at the exact right place and time, working in the exact right mediums and genres at the exact right point in the history of media, to play the one true “avant garde artist” to somehow reach everyone and become a global household name synonymous with…

Actually, I’ll let Agent Cooper say the word.

As a member of the Bureau, I spend most of my time seeking simple answers to difficult questions. In the pursuit of Laura’s killer, I have employed Bureau guidelines, deductive technique, Tibetan method, instinct and luck. But now I find myself in need of something new ... which for lack of a better word we shall call ... magic.

David Lynch arrived, by golden space-orb, at the perfect time in history to bear the black mirror and hold it up to us. To see between the worlds and beneath the surfaces. To ask us all, with total compassion, to see what we needed to confront in ourselves.

But we’ll come back to that.

David Lynch the Eagle Scout, born in Missoula, Montana on the off-cycle first postwar Inauguration Day, calls himself a “Capriquarius.” He loves sunny American dreams like the idyllic gee-whiz 1950s suburbia of his childhood spent across half of the US; and the static weather and gleaming promise of Los Angeles, where he’s spent the latter length of his career. And he loves these things completely without irony.

Though some fans, for a time, approach his work through an irony-tainted lens, he’s always insisted that he doesn’t understand irony. The irony we may project onto his work is a marker of our own discomfort — our own internalized shame — around whatever his earnest appreciation, curiosity, or empathy asks us to gaze upon.

Yet with that same steady gaze, David Lynch never ceases to examine the things he sincerely loves with a keen, intuitive interest in what their outer veneers may conceal. It’s long been a trope to say that much of Lynch’s work explores the “dark underbelly” of suburban Americana, and later, the “dark underbelly” of Hollywood. Though it’s all true, I’d like to revitalize it: the key is to recognize that his interest in the sunshine and the shadows it casts are both sincere; not in any contradiction; and in fact, of a piece.

He loves suburbia, and he sees the gnashing bugs in the green grass. He loves LA, perhaps more than anyone else ever has, or will, or can — and he sees the woman in trouble, stumbling under the palms of the Hollywood Hills or across the stars of the Walk of Fame. He loves the history and possibility of Hollywood — and he sees the seedy diner off the strip, and the filthy dumpster behind the diner, and the woman living in a kind of half-night beside the dumpster. (Is she the one who’s doing it?)

Not but, but and.

“One and the same.”

David Lynch is the true dreamer: he embraces the dream; he embraces the nightmare.

The word duality gets thrown around in a lot of discussions of Lynch, with varying degrees of thought toward what is actually meant by it. That’s one trope I especially aim to avoid. But many of the artists that have most resonated with me share this crucial quality: a capacity, even an insistence, toward holding such ostensibly exclusive truths at once. I like to describe certain works as “both an homage and a critique.” And though art as an analytical critique is antithetical to Lynch’s modus operandi, he helps us realize that a sincere, complete love for anything must confront its darkness.

Another auteur-Magician held in such universal regard in his medium is British comics author Alan Moore, whose iconic Watchmen is the ultimate paragon of “homage and critique as one.” I’ve long contemplated a twenty-year-old quote about Moore and his and Watchmen’s many imitators, that applies equally well to Lynch. Emphasis is mine:

But "Watchmen" has another legacy, one that Moore almost certainly never intended, whose DNA is encoded in the increasingly black inks and bleak storylines that have become the essential elements of the contemporary superhero comic book--a domain he has largely ceded to writers and artists who share his fascination with brutality but not his interest in its consequences, his eagerness to tear down old boundaries but not his drive to find new ones.

This carries us toward one of the most important throughlines across all of Lynch’s body of work, transcending all the turning points and thematic pivots between chapters in his filmography. There’s a name for the consequences of violence.

But again — we’ll come back to that. That lesson clicked for me later, long after a set of beautiful formative experiences with Lynch that cemented my trust in his insight.

David Lynch brings people together.

By the time I was in my late teens in the 2000s, several people had assured me that I was going to be all about this David Lynch guy. It came up frequently enough that, in retrospect, it makes me feel nice about whatever energy I must have been giving.

Around 16, a writer classmate gave me a printout of David Foster Wallace’s famous (or infamous?) essay about being on set for production of Lost Highway. “You’re gonna love David Lynch.” The biggest takeaway that has always stuck with me, for over twenty years, was a bit where Wallace acknowledges Lynch’s clever use of a physically deteriorating Richard Pryor as a metatextual visual of the fracturing and mutability of identity. Wallace goes on to question whether this casting is unethical, no matter how powerful it may be. (There’s that frank capacity for both admiration and critique again.)

It’s interesting to consider that this might have been my first real context for Lynch, other than broad Twin Peaks references I had seen in pop culture in my childhood.

I had a friend whose circle were all a little older than me, a couple towns over, and the coolest, punkiest kids I’d ever met — who were all into Lynch. With them, I’d catch brief glimpses of Blue Velvet and Twin Peaks. Observing a scene at the Roadhouse featuring Jacques Renault, I believe my friend described him as “one of the bad guys.”

A lightbulb spliced in over my head and zapped on with red light. I was surprised that media characterized by so many people as deep, high-minded Art™ would have “bad guys.” Long before thorny terms like “elevated horror” would emerge around works like The Babadook (a masterpiece that draws in part from Lynch), this was my first hint that artistry, depth, and respect were not inaccessible within genre storytelling.

As a child of the 90s, “genre” effectively comprised all the media I’d loved thus far in my life — or at least, all the media through which I actually learned to love storytelling.

In looking back, it feels like the direction I was heading had always been set out for me.

After two or three years of this adjacency, one fateful afternoon my friend finally sat me down — and they went right ahead and showed me Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me.

That day, my world changed completely and irrevocably. It felt like I’d discovered what movies were supposed to be like. It expanded my sense of what was possible in media, story, and art. It dramatically expanded my sense of what was possible, period.

If you’re reading this, you probably know that starting with Fire Walk with Me spoils numerous elements of Twin Peaks, including the central mystery: “Who killed Laura Palmer?” Arguably, even knowing that the killer’s identity ever is revealed is a spoiler, given that Lynch and Frost originally intended to never explicitly tell us the answer.

I’ve said many times that I would never introduce someone else to Twin Peaks in this way — but I’ve met a surprising number of people for whom FWWM was also their introduction to Lynch or to TP. And it gave me a very unique side door into his world.

I didn’t learn for some years that the film was considered a flop and a disappointment at the time of its release. By not having any prior expectations and just engaging with it as a feature film on its own terms, I was able to surrender myself to it. On the one hand, I experienced it as horror, and supernatural, and even a twist on the “haunted house,” yet also beyond any of those boxes. On the other hand, I experienced it as incredibly grounded in reality, and in profound empathy, in ways I had never seen.

Experiencing the film that way was also, in many ways, “more Lynch than Lynch.” While some images arrive as contextless in the moment — like talking monkeys and extreme closeups of mouths — others that hit similarly turn out to have significant, plotty prior context in the series, like the letter under the fingernail. Via this double-heightened sense of being thrown in the deep end, I noticed two key things with surprising clarity.

During the early scene at Hap’s Diner, with the crackling electrician and whispering Frenchwoman, I still remember saying, “He seems to have a ritualistic sense of rooms.”

Even earlier, I see Lynch onscreen for the first time as Gordon Cole, communicating with his agents through the abstract performance of Lil the Dancing Girl. When Agent Desmond then breaks down Cole’s coded messages for Agent Stanley, I actually exclaimed to my friend: “Is the movie telling us how to interpret itself?”

I still think of that scene as a cipher to some of Lynch’s cinematic language. It shows us that some of what we see will be simpler and more literal than we might imagine — “I mean it like it sounds, like it is” — and that some of what we see will be signals almost arbitrarily associated with a certain element or theme. And yet even after all that, some of what we see must never be explained: “I can’t tell you about that.”

These moments of conversation with the film and its auteur were remarkable partly for how the film connected with me in a vacuum, and partly for how they reflected my first time thinking about cinema this way: “Someone made this. What are they saying?”

I immediately became obsessed and started renting as much David Lynch as I could find and, crucially, making all my friends watch it with me. I rushed to watch Blue Velvet and Mulholland Drive with a few other teens in a single afternoon. (I was initially disappointed that these two had somewhat less “overtly weird” imagery than FWWM.)

To press onward, I had to go rent the fucking VHS tapes of the original series one after another. (Obviously, I never returned them.) Then I had what remains to this day one of the most beautiful, miraculous, and joyous media experiences anyone has ever had.

I somehow gathered pretty much all of my friends to binge Twin Peaks together, in a magical flurry — over a few nights? a couple of weeks? — in one girl’s cozy, wood-paneled living room that always smelled a little of evergreen trees, visible outside the sliding glass door. Her parents, who were always so kind and welcoming to the whole rotation of misfit punks and goths she and her sister would bring around, would pop in occasionally. The first time, one of her parents remarked to the other how amusing it was that we were discovering the show, which they had watched in its original run.

This period still lives large in my memory as one of the happiest times in my life. I got to experience what would become My Favorite Thing Ever, for the first time, with all my friends, in a shockingly resonant setting. And because I already knew who the murderer was, I received a masterclass in the art of mystery writing — watching all my friends be deftly misdirected by red herring after titillating twist after heartstrings tug.

One of the most brain-changing moments of my life, as a lover of story and later a filmmaker, was when a lifelong best friend literally jumped up out of his seat with excitement, shouting of the eventual killer: “I really hope it isn’t [them]! I like [them]!”

Amusingly, when that friend had arrived late, after the legendary Red Room scene had already passed, my other lifelong best friend gave the only teenager-y razzing I recall from anyone until Season 2: “It’s the most pretentious thing I’ve ever seen in my life!”

This may seem like a loosely connected series of vignettes about my on-ramp into Lynch’s world. But as I look back on these memories with twenty years of hindsight, and today’s context, the picture changes. Even if some friends back then groaned at certain aspects, almost all of them would go on to remain Lynch fans to some degree.

Many became fluent in his whole filmography, as I did. Some didn’t stay as actively engaged, but tuned back in with fond enthusiasm for Twin Peaks: The Return. And I seriously doubt there was one single person among my friends back then for whom those films and that series did not retain a special significance for the ages.

What other filmmaker do a bunch of 18-year-old punks and metalheads get worked up like that about? Especially back then, when indeed, teens largely defined ourselves by our taste in music, and the auteur filmmaker (much less the auteur showrunner) was a new or foreign concept to most people — largely one popularized by Lynch.

David Lynch’s work has at times been labeled “pretentious” or “hard to understand.”

But I think pretending to anything is the last thing he would ever do. Precisely to the contrary: I think the reason people get so excited to discover his work, to introduce others to it, and to form bonds over it and identities around it, is that whether or not every aspect is for you…everyone understands on an intuitive level that what they are seeing is someone who always expresses himself authentically and unapologetically.

We live in a society that has structurally pressured almost everyone alive to suppress ourselves in some aspect; to mask as things we are not; to fit into boxes and closets and eggshells; to “function” in ways no one should have to. This is one way hierarchies hold, because self-actualization is inherently disruptive of dominance and power-over.

But the shapes and sizes of those boxes has narrowed ever tighter, and the force with which we are crammed into them has accelerated exponentially. First, since the dawn of industrialization — an era functionally synonymous with the age of cinema.

And again, since the anti-collectivist construction of the postnuclear suburban fantasy. This is a deeply performative social order in which the “nuclear family” recreates the power dynamics of the state. For enforcing rigid, prescribed modes of manhood and womanhood well, and spitting out babies that are indoctrinated into such a hierarchy and exploitable as labor, the family patriarch is rewarded with his very own borders.

A shiny green lawn with a white picket fence in the sunshine. Where friendly faces drive past on bright red firetrucks, to protect you — far from cities. Far from scary noises; strange, rhythmic, impersonal machines; and visible disenfranchisement.

Far from anything that would reveal how labor really upholds profit and power. Far from anything that would reveal the picket fence’s role in anyone else’s suffering.

This social order’s era is the one functionally synonymous with the time of David Lynch.

No surprise, then, that Lynch idealizes suburbia, yet sees how it operates as a facade. Or his fascination with gender roles and their more performative expressions. Or that his rite-of-passage ordeal was life in industrial Philadelphia, where he became a father.

I’m tying these first two premises together, but we’re still talking about why Lynch’s work, for its seeming “darkness,” brings people together with such enthusiasm and joy.

All of this is to say that in the entirety of living memory, and today more than ever, people are deeply moved and enthralled by any chance to witness someone who is actually…actualized. Expressing themselves earnestly. Unapologetically. Deeply.

We desperately yearn to see someone — anyone — really, really, really living.

And we can’t help but be compelled by work that affirms the deep, intuitive sense most of us have, though many cannot articulate why, that something is really wrong.

When we get the rare privilege of seeing someone’s Light shining bright, and on the truth — and if we’re not too afraid or self-blaming about the mirror it holds up to our own suppression — we want to bask in that Light and bear it excitedly unto others.

And so it is that today we’re realizing basically everyone in the entire world who has not given up on the human Spirit is unified in love and admiration for David Lynch.

So it seems to me that touching people in their deepest corners, and holding tight to hope and love even as we confront life’s horrors, is not so hard to understand after all.

David Lynch is not “weird.” He’s just looking closer.

In the next few years after those dreamlike days, as a confused young woman trying to figure out why I felt so stuck all the time, I did a lot of road tripping around the US. The first couple of times involved several of those friends, many of whom I remain close with across time and space. Eventually I worked up the nerve to fulfill a dream I’d had since age 16, and drive around most of the country entirely alone.

I grew up somewhat sheltered and in a densely populated place. So exploring the rest of the country by car, especially alone, was a life-altering act of self-education. By that point, my image of Middle American, rural, or small-town life was largely built from Lynch’s depictions: by turns romantic, tragic, nostalgic, lonely, communal, deprived.

During these explorations, I started cracking one of my oldest hot-takey bitch-isms:

“David Lynch is a documentarian.”

But what does she mean by that?

It would be a very long time before I would have the vocabulary to expand on this zinger the way it deserved. But what I was pointing at was the fact that while, yes, some of his imagery is certainly surreal, or repetitive, or surprising, in ways that defy everyday experience…the more I grew up, and the more of the world I got to witness, the more his feel for how people and places operate just seemed self-evident to me.

We’ve all heard his characters and settings — or him — described as “eccentric” or “weird.” Often, professional critics go much, much farther: “Abandon all hope of logic, ye who enter here” because, of course, there are “few places creepier to spend time than in David Lynch’s head”! For curiosity, I just tried searching the terms “david lynch mind of a madman.” And to my frustration, so many things come up that I even found one professional art critic commenting on exactly that phenomenon six years ago.

Sometimes people make these remarks out of sincere bewilderment. Sometimes they mean it as a compliment to his point of view. But after having to actually type those words back here…sometimes it just feels disrespectful or downright cruel.

Another bit I’ve always remembered from Wallace’s essay was that Balthazar Getty, who played Pete Dayton, did an impression of Lynch behind his back that Wallace found mean-spirited. (Getty later played Red in Twin Peaks: The Return, so it seems he and Lynch remained friendly. We all do things when we’re young that we grow out of.)

And I’ve done the Lynch voice too, with affection. I’m sure many of us have. But at some point, I stopped — because I couldn’t be sure why a given person laughs at it.

The following probably can’t help but sound a little grandiose in an essay I’ve titled “David Lynch Is the One True Immortal Goddess-Empress of Herstory,” but it’s true:

As I grew closer with Lynch’s work, probably around Inland Empire, a switch flipped. When I hear these florid exclamations about how supposedly weird and confounding David Lynch is, I now can only identify with Lynch and not with the person speaking.

His reality makes a hell of a lot more sense to me than any reality from which his, in the year of our destruction 2025, would still seem sOoOoO weird and confounding. And sure, I won’t deny that I get some degree of satisfaction from this thought — but for the most part, what I’m describing is a pretty alienating sensation.

When you call a public figure “weird,” how are people who share parts of that human being’s experience supposed to feel about themselves?

When you call a visionary artist, who’s universally respected even by people who don’t enjoy their work, “weird”…what are you even saying about yourself?

How was this ever an acceptable form of discourse about public figures?

Much less about the most important filmmaker who ever fucking lived?

I think it’s long overdue that we kill this trope and someone speak the truth:

David Lynch isn’t fucking weird.

He’s just actually paying attention.

David Lynch asks us to look at things we’ve been taught not to think about too hard.

David Lynch notices, and allows himself to question — and invites us to join him in questioning — certain things we’re all culturally pressured to take for granted.

I think the narrative that he’s so “weird” boils down to three main axes. Depending on who you are while reading this, at least one of these observations might hurt your feelings. But I sincerely do not mean any of this as a criticism or judgment on anyone.

First, let’s be frank: professional media critics as a class are a little more likely to come from a relatively sheltered and population-dense walk of life — just like I did.

There’s nothing wrong with that — but any single point of view is inherently limited. And when you multiply a point of view across a whole field of discourse…it gets weird.

Lynch’s life history spans numerous walks of American life and beyond, which gives him a more refracted lens on things than most people. Even at the time of just his debut feature Eraserhead, consider the two biggest puzzle pieces of the David Lynch origin story: he grows up all around the US because his father worked for the Forest Service, a childhood he describes in very idealized terms; and then he experiences a dramatic culture shock upon moving to a troubled neighborhood in Philadelphia.

Second, I think people see David Lynch as “weird” because he’s breaking the rules.

The society we live under does not want us to interrogate the causes or consequences of violence. The society we live under does not want us to wonder what’s under the hood of midcentury suburbanization or the industrial production of entertainment. The society we live under does not want us to pay close attention to human behavior.

I said earlier that when we relate with Lynch’s work through a filter of irony, it hints at our own internalized shame. I’d say the same about this nasty business of calling people who don’t fit rigid cultural norms, or the ways they express themselves, “weird.”

Both are means of posturing ourselves as above and apart from that which, for one reason or another, makes us uncomfortable to sit with and simply acknowledge.

In Blue Velvet, a traumatized Jeffrey asks: “Why are there people like Frank? Why is there so much trouble in this world?” I hear the earnest pain of this question as Lynch’s own. This should come as no surprise; he spent his whole career asking it through art.

And of course, the blame for these projections and acts of distancing should as always be pointed at systems, not individuals. When the society you live under wants you to believe “people like Frank” are just born that way and that it’s thus their fault there’s so much trouble in this world…it’s understandable to grow uncomfortable reflecting on the Franks out there — which risks being seen as excusing or being one of them.

And finally, the deeper point this all builds toward:

Calling someone like David Lynch “weird” is simple ableism.

I won’t venture to put a label on him. But we’re talking about an artist who has spent his entire career questioning unjust or troubling things that are accepted as normal…

…crafting honest depictions of reality as he sees it, as uncomfortable as it makes us…

…and generally being in tune with his own inner compass to the exclusion of any societally constructed script or unspoken ruleset.

You may draw your own conclusions about what to call a neurotype like that. But I do know what I call mine, and all of the above is part of why I’ve always related with him.

But even if David Lynch is perfectly “neurotypical,” the knee-jerk response of calling his patient, compassionate, insightful portrayals of human behavior and interiority “weird” is…still rooted in socialized biases. We’re taught to other people whose ways of being, and seeing, differ from those our society deems convenient and profitable.

This brings me back to my first thesis. A defining trait of the Shaman archetype is that a Shaman has, by some means, accessed alternative points of view — becoming a steward of perspectives for the literally “uninitiated.” A dweller between two worlds, who helps to shepherd others safely across the threshold — and reintegrate after the psychedelic ordeal of such a rapid expansion of the mind, and thus, the world.

One who helps us face our doppelgänger, our shadow self, with more perfect courage.

I’ve written much about my distinct lens on Shamanism and how it intersects with storytelling and mass media — including, by no coincidence, a newer but instantly iconic pop culture character so defined by these tropes that “Weird” is in her name.

As a Transgender woman and organizer of Trans community, I speak often about Transness as inherently a process of shadow work. You’re more acutely forced to confront your shadow when parts of it are palpable in your body; perceptible in the wrongness of every social role that’s ever been put on you; visible in the literal mirror.

I further assert that Transgender people are inherently Shamans and Magicians — inherently storytellers — for the story our visible self-actualization tells to all who are blessed with the privilege of bearing witness to us. Every single Transgender person of any gender, just by standing in their truth, tells the most important story in the world: that it actually is possible to love yourself completely and insist on what you deserve.

I'll miss the sea, but a person needs new experiences. They jar something deep inside, allowing him to grow. Without change something sleeps inside us, and seldom awakens. The sleeper must awaken.

Parts of transphobia are rooted in the panic and internalized shame of those who can’t take the mirror our awakening holds up to their own state of half-sleep. Our bright, shining Light should offer every person a beacon of hope that a life of true agency is possible. But some are so mired in self-blame for their own oppression by power structures — or in fear of their own truths and those truths’ consequences — that their reaction is to flee, deny, and attack: “If I can’t have it, no one should.”

I must not fear. Fear is the mind-killer. Fear is the little-death that brings total obliteration. I will face my fear.

I dive into Trans Justice at this point in the story for two reasons. First, diversity of gender experiences is inseparable from Neurodiversity. And one way this womanifests is how our visible liberation from norms is often, likewise, dehumanized as “weird.”

The other reason is that upon searching for the dialogue from Deputy Hawk below, which introduces the Black Lodge and has an overtly Shamanistic lens, I realized it’s immediately followed by the first introduction of Special Agent Denise Bryson. Like most Transfeminine characters at the time, Denise was unfortunately played by a cisgender man in “transface.” But she was perhaps the most sensitive, humanizing, authentic portrayal of a Transgender woman in pop culture in the 90s (or long after).

It’s powerful for me revisiting Hawk’s quote through my lens on Transition as shadow work — which is perhaps even something that episode writers Lynch, Frost, and Barry Pullman were intuitively grasping toward via this juxtaposition. One can easily see how this Hawk passage — a pseudo-Indigenous fictional cosmology informed by Mark Frost’s Jungian and Theosophical leanings — pertains to much of what I’ve discussed.

But you can also pretty much just straight-up replace “Black Lodge” with “gender dysphoria” and “White Lodge” with “Gender Euphoria”:

The White Lodge is a place where the spirits that rule man and nature here reside. […] They say it exists only on the spiritual plane. […] There is also a legend of a place called the Black Lodge: the shadow self of the White Lodge, a place of dark forces that pull on this world. A world of nightmares: shamans reduced to crying children; angry spirits pouring from the woods; graves opening like flowers. […] The legend says every spirit must pass through there on the path to perfection. There you will meet your own shadow self. My people call it the Dweller on the Threshold. But it is said that if you confront the Black Lodge with imperfect courage, it will utterly annihilate your soul.

We’ve driven down a long, winding road through the hills.

But all of this inevitably brings us — back — to my final thesis.

The thing I kept saying, so many words ago, that we would come back to.

The thing we always come back to.

The thing David Lynch insists over and over that we must come back to, every time he returns to Twin Peaks — no matter how many of us resist the uncomfortable truth.

David Lynch knows it all begins with trauma.

A few years after beginning my journey with David Lynch, I was driving down a long, dark, narrow highway at night, with my then-girlfriend. We had recently watched Blue Velvet together, a first for her, and we were unpacking our understandings of it.

She highlighted a line that, in three or four years living with the film, I had never really noticed or given much thought: the moment Frank says to Jeffrey, “You’re like me.”

Another lightbulb spliced in over my head and zapped on, this time with blue light. We talked about Frank’s shifting use of titles like “Mommy,” “Daddy,” and “Baby,” and parallels and contrasts between his and Jeffrey’s respective involvement with Dorothy. This is probably also when I began to unpack the significance of his crying at the club.

A framing I came to, which was central to my interpretation for years, was that Lynch was conveying nuanced, realistic sociological layers behind different forms of violence and suffering — without calling too much attention to it. They weren’t things you had to notice or process to enjoy the film; they were just there, if you wanted to find them.

I think of it in simpler terms now: David Lynch peers into the darkness to understand where violence comes from. And if you do this with clear sight, you will see trauma.

In my early Lynch days as a teenage girl with “gifted kid burnout,” I was shocked and confused to learn he says he’s not an “intellectual.” But of course he isn’t; art is not intellectual. A quote from his book on meditation and creativity, Catching the Big Fish:

Life is filled with abstractions, and the only way we make heads or tails of it is through intuition. Intuition is seeing the solution — seeing it, knowing it. It’s emotion and intellect going together. That’s essential for the filmmaker.

“Emotion and intellect going together.” Hold onto that with me.

This is the closest I’ll come to a story spoiler. It involves some of the lower-screen-time characters in FWWM and “Part 6” of Lynch and Frost’s Twin Peaks: The Return.

In “Part 6,” sometimes labelled as “Don’t die,” we endure one of the most horrifying deaths in the series. It’s witnessed by trailer park manager Carl Rodd, whom we first met in Fire Walk with Me, where we observed him enter a distant state that seemed connected to the Red Room. “I've already gone places. I just want to stay where I am.”

When Carl witnesses the truly senseless death of a pointedly innocent person, he sees an aura of golden light float away. There’s something here about a spirit subjected to violence, yet released — as in, not traumatized like those left wailing amid the tragedy.

That golden color is a powerful recurring motif across The Return. If its significance has not begun coming into focus yet, it takes on new meaning a few episodes later.

The episode ends with another intense scene, where a callous police officer, pointedly nothing like the warm original Twin Peaks Sheriff’s Department cast, speaks with deep cruelty about the death of an offscreen character who “couldn’t take being a soldier.”

Though there are several iconic episodes of The Return with far more jaw-dropping impact, this episode left me quietly stunned. I felt like I’d seen the thesis of Twin Peaks.

To my eye, Lynch seems to seek out two things in Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me.

Outside the text, I think he strives to “take back” agency over a project that had spiraled a little out of his control, involving far more cooks in the kitchen and institutional meddling than anything he’d worked on since his formative artistic trauma directing Dune — after which he swore to never do another studio picture.

And what is a network television series but a studio picture with even more studio?

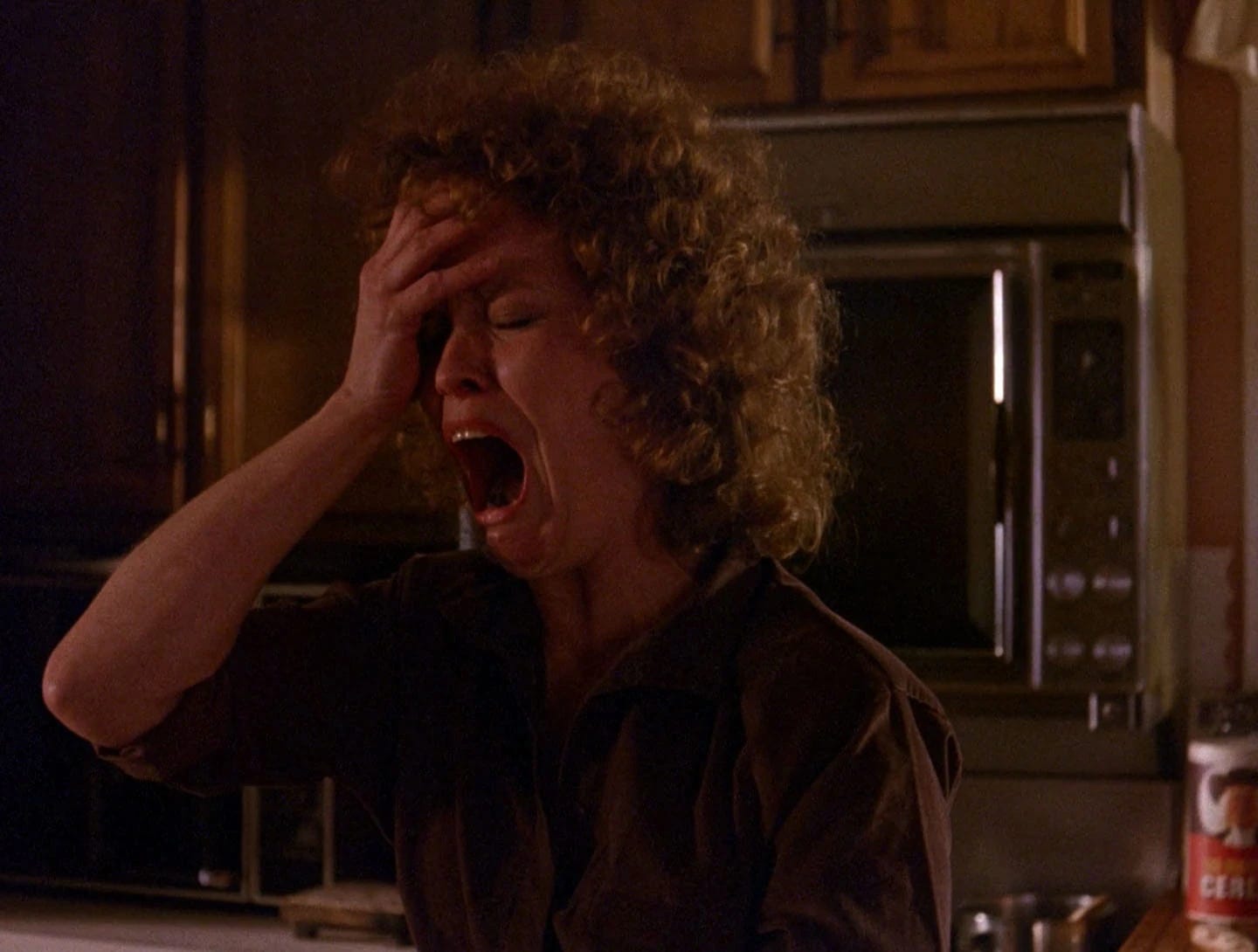

Inside the text — from the very first image, blue static that slowly pulls out to reveal a television smashed by a murder weapon — I think he seeks to recenter Twin Peaks around its true origin point and spiritual center: the abuse and trauma women suffer.

Around Laura.

These twin aims are one and the same. To me, they suggest a frustration with others defining Twin Peaks yet missing its core. Executives, collaborators — and the audience.

The Log Lady Intros that were later appended to precede original series episodes were written and directed by Lynch. And he’s always said that for him, the 90-minute “Pilot,” also known by the series’ original title “Northwest Passage,” was the real Twin Peaks.

So what did he have the Log Lady say into camera, after the fact, to set up the pilot?

To introduce this story, let me just say it encompasses the all — it is beyond the "fire," though few would know that meaning. It is a story of many, but begins with one — and I knew her.

The one leading to the many is Laura Palmer. Laura is the one.

This is precisely what audiences in FWWM’s day reacted against. Sure, maybe they were also exhausted by Season 2 (the lopsidedness of which is a little overstated).

But really, I think audiences who in 1990 had bought into the pilot’s “quirky humor” and plucky Coop and soapy drama and thrilling mystery, were just not yet prepared in 1992 to bear witness to the cycle of unspeakable trauma otherwise mostly alluded to.

But that is the heart of the story.

Because I entered Twin Peaks via Fire Walk with Me, this has always been clear to me.

Twin Peaks is about a lot of things. It’s a mystery. It’s about mystery. It’s about the hope, it’s about the sadness, it’s about love. It’s about Magic. It’s even about television.

But at its core, it’s about the causes and consequences of violence — against women.

"The evil that men do. Maybe it doesn't matter what we call it."

Most importantly, Twin Peaks is the story of Laura Palmer.

The one leading to the many.

The role of the Shaman in the ordeal is to hold you through it. Not let you look away.

After living with Fire Walk with Me for over two decades, last year I finally saw it on a big screen. There was a screening at LA’s Egyptian Theatre for a series called Bleak Week: Cinema of Despair — featuring a lovely live conversation between The People’s Joker filmmaker-star Vera Drew and the great Ray Wise, of Twin Peaks and beyond.

I’d seen FWWM countless times before. And considering that it’s by far the single most impactful film of my entire life, it remains the piece of media I’ve written the most about. There was a period of years sometime in my twenties during which I probably could have rattled off a scene-by-scene summary of the entire movie.

It was a packed house. To finally watch my most defining film on a big screen, in an opulent 102-year-old theater in Los Angeles, filled with people who shared my love for it, was a thrilling feeling. I ran into a bunch of friends and sat with them to watch.

But there was something I didn’t anticipate. I had never asked myself what it might be like to watch such a visceral depiction of tragic, horrifically intimate abuse…in a room full of other people.

Total strangers.

For the entire credit roll and beyond, the room was dead silent. Shellshocked. Even though, I’m sure, almost everyone present had seen the movie multiple times before.

I cannot remember any other crowded theater so silent at the end of a film.

This is what the Shaman does.

In returning to Twin Peaks one last time, Lynch and Frost again recentered Laura and her trauma, albeit in a different way. If Fire Walk with Me sometimes seems to say “You’re missing it, you’re in denial, look closer”…then The Return sometimes seems to say, “You need to let go. If you can’t release the past, you’ll just keep going in circles.”

“Appetite, satisfaction; a golden circle.”

“With this ring, I thee wed.”

“Don't take the ring, Laura. Don't take the ring.”

Through intuition — emotion and intellect going together — David Lynch sees, and shows us, that only by confronting, processing, and integrating our trauma, will we ever escape the cycle. Only by that process will there ever be less trouble in this world.

We can’t deny the past. And we can’t change the past. And we can’t live in the past.

Don’t forget where the prequel film’s title first originated:

Through the darkness of future past,

The magician longs to see.

One chants out between two worlds,

Fire, walk with me.

Of course, Lynch is always “diving deep” — which also means operating on many levels. And of course, he always wants to leave us “room to dream”: as much freedom as possible to continue exploring and inhabiting the work with our own intuition.

We can engage with these layers of Twin Peaks through the lens of the in-fiction story. The lens of its implications for our own lives. Even the lens of our expectations of, and relationship to, David Lynch himself and his body of work. And countless other ways.

So I want to conclude this with the closest I’ve come to connecting with him in person.

I haven’t met David Lynch up close. But I have seen him live, twice, on his speaking tour in 2007. At one of those dates, there was a Q&A where I got to hop on a mic in the crowd and ask him a question. I’ve always been a little embarrassed that I lobbed him a total softball. At the end, I waited around to try and meet him, but I missed him by five minutes. Another woman, with fiery red hair and a chevron-print coat, got his autograph on her calf and said she was going to get it tattooed on the next day.

But the real takeaway was something he said incredibly nonchalantly onstage.

When I saw him speak, he actually outright verbalized one of the most prominent recurring motifs in his work. It’s a topic debated by fans, but the work itself never makes it too explicit, and I can’t find any sources online where he says it anywhere else. It was an uncharacteristically direct tipping of the hand by the artist who believes you should never say too much about “intent” or sew up the mystery at the end.

I don’t remember what question he was asked. But he does his sort of jazz-hand fingers of excitedly searching for an idea, an almost antenna-like gesture, and says:

“I’ve always been fascinated…by this idea…of electricity…as a doorway between worlds.”

My jaw literally dropped.

Decades later, I’m no longer just amazed by its implications for his work. Now I sense that by his own intuition, he actually figured out something elemental about our world.

To close this piece about Lynch as the Shaman of our collective nervous system in the age of humanity’s post-atomic spiritual trauma, I leave his words’ significance to you.

Room to dream, and all.

I think that ideas exist outside of ourselves. I think somewhere, we're all connected off in some very abstract land. But somewhere between there and here ideas exist.

David Lynch is eternally hopeful. I think.

In that abstract land of pure consciousness, I hope David Lynch finds rest and bliss.

But I find it much more likely that as soon as he finds his footing, what he’ll want is to get straight back to work. From his Masterclass:

And so you just stay alert, do your work, don’t worry about the world going by. It doesn’t mean that you can sit around and not do anything; you’ve got to get your butt in gear and do it. And don’t take “no” for an answer – translate those ideas to cinema, or to a painting, or to whatever, and figure out a way to get it done.

To be honest, I simply have to hope he will. Because I really don’t know what we would do without the most powerful Magician of our lifetimes and our age, among the few who have actually sought to use their gifts for the benefit of everyone.

The future past this evening is clouded with darkness. We need some Light to guide us.

I think one thing that has actually been hard to understand about David Lynch, for many people, is how relentlessly hopeful he is. He always believes in possibility.

But in his last cinematic work, Twin Peaks: The Return, it could be interpreted that he and collaborator Frost see a certain dying of the light. A sun setting on the dream.

I can’t seem to find it, but a few months back my brother mentioned a quote from Lynch that again sounded unusually direct — about Twin Peaks: The Return expressing some feeling of the darkness growing, perhaps about “fighting in the street” and losing. It was so pointed I was initially certain it must be a quote from Frost. It felt resonant for me with Janey-E’s comments about the state of society in The Return.

I can’t find it anywhere. The closest I can find is a Cahiers du Cinéma interview where he brushes against it, framed with his spiritual lens on the Hindu dark age, Kali Yuga:

INTERVIEWER: The series is also very realistic compared to America today, at the time in which we live...

LYNCH: It's a dark age... we can hope that it will light up but for the moment it's very dark.

I’m used to Lynch’s perspective sounding more like this:

“Don't even worry about the darkness. Turn on the light and the darkness goes.”

What does it mean when our most hopeful Seer feels like we’re losing the fight?

2025 was already a scary year before it started. I am a Transgender woman in a dying empire that’s scapegoating my community for the mass suffering caused by neo-feudal capitalism. This Inauguration Day, tomorrow — quite possibly the last — will mark a dramatic escalation in this country’s ongoing construction of our genocide.

Mark my words: great horrors are coming.

Hardly a week into 2025, Los Angeles, a place I’ve learned to love almost as much as David Lynch does — the place where I finally found my joy, my voice, myself, my people, my purpose — was set ablaze. By oil profits, by genocidal militaries, by software designed to obsolete artists and overwhelm our species with propaganda.

The air, especially indoors, is still full of a historic virus our institutions have gaslit us about for five years — which made it unsafe for David Lynch to leave home or direct.

Yet outdoors, our air is now also full of urban-fire toxins that aren’t measured on any air quality metrics in operation, which are likely to not just poison our lungs, and our eyes, but to stick to our hair and clothes and cause unpredictable long-term illness and death — just as 9/11 killed more people in the years afterward than on the day.

The air is, both figuratively and literally, on fire.

And then, just to make sure the message was really driven home, they were forced to uproot David Lynch. And now I just don’t know what is left to look forward to in this post-apocalyptic world. The future seems more scorched engine oil than sunshine.

Have the Angels all gone away?

I often say that gender dysphoria is like a long, dark, narrow tunnel you can’t see the light at the other end of. When you can’t even be sure there’s a way out, taking that first step forward — that first step of Transition — is an act of faith.

But there is a light that can guide us and assure us of a world outside our tunnel, in which to thrive: the Light of our siblings, shining bright, free of their own dark tunnels.

Right now, for me and for many, that dark tunnel is what the entire world feels like.

David Lynch has always shined as bright as anyone can. If we are to press forward through the long, dark hallways of this frightening new age, we must be able to hold faith that a Light like his remains forever shining.

His death almost feels like a test of that faith. Because if his can’t, whose can?

It’s a lot like gender, or any kind of self-actualization: the bad guys — and there are bad guys in this enduring drama — want you to think your Light is already snuffed out.

The secret to breaking their spell is realizing no one’s Light can ever really die.

To some reading this, these threads may not all feel connected.

But David, more than anyone, has shown me that it’s always, always, all connected.

David Keith Lynch is the greatest artist of all time.

He is the one person in our history who natively speaks the language of cinema — a language that had only been developing for about fifty years before he arrived.

He made the two greatest films that have ever been made: Mulholland Drive and Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me — which are equal in measure and have no other peers. There is no other filmmaker of his caliber, and there are no other films “like his.”

He made the two greatest TV series of all time: Twin Peaks, and then Twin Peaks: The Return — which actually outdoes the original, while in the same breath also making the original better. Each is so far ahead of its respective time that, now that we have both of them, there’s no point adding to the list. Television is, at this time in history, essentially just the medium that was devised so that Twin Peaks could materialize.

A vision like his can never be replaced or emulated, only witnessed and learned from. Let us strive to do as he’s asked and sit patiently with the discomfort, to find the hope.

Yet as much as he loves the theater of the absurd, little is as absurd as seeing him as only a filmmaker. In one sense, he is not a filmmaker at all, unless the Sun is only the warmth it gives you; unless the Magician is as little as “someone who casts spells.”

In another sense, he is the only filmmaker who ever lived.

David Lynch does the impossible: creates Fire from pure Air, sparks Light into a world of darkness. He paints Angels of hope for those whose tender boughs of innocence have already begun to burn. That fire is very hard to put out — yet he never gives up.

Before we assume our respective roles in this enduring drama, just let me say that when these frail shadows we inhabit now have quit the stage, we'll meet and raise a glass again together in Valhalla.

In The Return’s special features, every single time a cast or crew member wraps, David personally calls “gather round” to bring everyone together in applause for them.

Well — it’s a picture wrap on David Lynch.

Let us gather round to celebrate his life — his work.

I wonder what kind of work he will do offscreen.

Because today, it really does feel like all goodness is in jeopardy.

You feel it too, don’t you?

I know you do.

Even if you can’t look right at it.

I hope we figure out how to carry forward his Light.

And I hope I finally get to meet him up close one day.

One of the first great lightbulbs over my head arrived via David Lynch onscreen as Gordon Cole — telling my teenage self that we would forever be speaking in codes.

Over a decade later, Twin Peaks: The Return aired — entirely within the first six months of my coming out as Transgender. There’s another special moment that I, like many of my siblings, have carried with me closely. Again, it arrived via David Lynch onscreen as Gordon Cole — but this time with one of those rare, unusually direct proclamations:

Fix your hearts or die.

It sounds different to me now.

I guess we’ll find out.

I’ll see you at the curtain call.

SINISTRA BLACK (she/her) is a Writer-Directress and organizer of Trans-centered Queer culture. She was voted Community Leader of the Year 2024 in Best of Sapphic LA.

crazy how poetic it is. the last hurrah of civilization was a four-day global outpouring of love and mourning for David Lynch, before the demons that live in the hearts of men burst forth and gave birth to a boiling sea of indescribable nightmares on his birthday